Class Year

2014

Preview

Creation Date

Fall 2012

Department 1

Art

Description

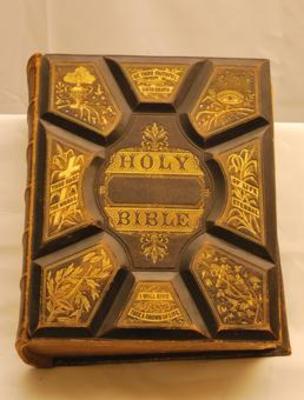

Illustrated Reference Family Bible

1873

Leather with Gold Embossing

12.75" x 10" x 4"

Musselman Library Special Collections, Gift of Thomas Cooper

In a time where religion dominated daily life and exploration continued to reveal a more expansive world than ever imagined, curiosity cabinets thrived. The yearning to know all led to the collection of many items from all over the world. Collectors sought to mimic Noah’s Ark by “abstracting the essential components of Creation into the confines of a man-made space,” thus creating a microcosm of the universe.[1] The Illustrated Reference Family Bible displayed in the Gettysburg Cabinet certainly evokes a time where it was believed that to know God, one must know the world.

During the Renaissance illuminated manuscripts were highly valued for their spiritual and artistic qualities. The Renaissance thirst for knowledge rekindled an appreciation of the old; ancient texts, therefore, became exceedingly valuable.[2] Many individuals sought out Biblical manuscripts written in languages such as Hebrew or Syrian for the beauty and mystery of the written language.[3] The Bible itself is actually quite strange due to the fact that it is most often read in a translation as opposed to other sacred texts such as the Qur'an which is almost exclusively read in its original Arabic. Therefore, translations of the text are quite common, and during the Renaissance, highly sought after.

In addition to the variety of languages these texts were comprised in, many of these manuscripts were also sumptuously covered. Some even had “treasure bindings” which could include minerals, precious metals, gems, and insets of ivory which increased their worth. [4] The Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612) collected many such manuscripts for his cabinet, the most famous of which was the Codex Gigas, made famous by its image of the Devil. [5] The illustration of the Devil is also why it is sometimes referred to as "The Devil's Bible." The Codex Gigas is the largest medieval manuscript known to date and therefore its illustrations are quite large and elaborate, adding to its value. This manuscript become part of Rudolf II's cabinet collection in 1594 when he borrowed it from a monastery. It became a permanent part of his collection when he simply did not return it. Like the Codex Gigas, many illuminated manuscripts functioned as a tangible representation of spiritual knowledge in the cabinets, as well as an item of both luxury and craftsmanship.

This Renaissance passion for knowledge led to a fascinating blend of the Bible and the encyclopedia. In 1540, the Geneva Bible became the first Bible to include encyclopedic elements such as maps of the Holy Land, charts of various kinds, and reconstructions of biblical architecture.[6] However, this was by no means the first time that the concept of an encyclopedia came to be. In AD 77, Pliny the Elder wrote Historia naturalis, arguably the first natural history encyclopedia. His book was rather comprehensive, including such topics as planets, plants, animals, medicine, minerals, arts, and still others. After Pliny, other scholars followed inhis footsteps, beginning to comprise their own encyclopedias. As time went on printing became faster and easier, and soon more and more encyclopedias were developed, including those found in the Geneva Bible and others like it.

By the 19th century “Family Bibles,” took this trend a step further, allowing owners to create their own encyclopedias of sorts. These Bibles incorporated pages for recording births, marriages, deaths, and family trees.[7] A seeming tribute to how Renaissance cabinets delighted in the beautiful and rare, these Bibles were frequently ornately decorated both inside and out.

The Bible used in this exhibit is a perfect example of such a Family Bible from the 19th century. The cover of this Illustrated Reference Family Bible is leather, embossed with gold and is in rather good condition, clearly meant to be displayed rather than stored away on a shelf. Its cover displays the images of an eye, an anchor, a trumpet, a lamp, a cross, corn and wheat, and a crown of thorns. The cover reads "Be thou faithful unto death, I will give thee a crown of life" and "Thou hast the words of life eternal," surrounded by various nature-themed designs. Colored images of plants, animals, and biblical scenes such as the temple in Jerusalem still retain much of their original hue. Inside are numerous tables, charts, maps, a concordance, an illustrated dictionary, and many more “study aids.” Also there is what appears to be very faint handwriting on a page dedicated to births and deaths. The biblical text is the King James translation and includes the Apocrypha[8]. Due to the Apocrypha’s placement, it is clearly a Protestant Bible.[9]

The family of Thomas Y. Cooper donated this Bible among his many rare books given to Schmucker Memorial Library when his papers were given to the College in 1967. This Bible remains a palpable culmination of the Renaissance quest for knowledge and its interest in both the spiritual and natural world.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Arthur MacGregor, Curiosity and Enlightenment: Collectors and Collections from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 57.

[2] Christopher de Hamel, Bibles: An Illustrated History from Papyrus to Print (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2011), 10.

[3] de Hamel, Bibles: An Illustrated History from Papyrus to Print, 131.

[4] Ibid, 45.

[5] Michael Gullick, Ivan Hlaváček, Jan Svanberg, and Anna Wolodarski. The Codex Gigas. National Library of Sweden, 10 June 2007. www.kb.se/codex-gigas/eng/

[6] Lori Anne Ferrell, The Bible and the People (London: Yale University Press, 2008), 82.

[7] Ferrell, The Bible and the People, 135.

[8] The Apocrypha, also called the Deuterocanon or “second cannon,” means “hidden,” and refers to a selection of books outside of the traditional biblical cannon. These books are accepted as Scripture for Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox churches.

[9] In Protestant Bibles the Apocryphal books are traditionally kept together and placed in between the Old and New Testament, whereas Catholic Bibles place the Apocryphal books in their canonical order.

Recommended Citation

Duranko, Jill, "Bible" (2012). The Gettysburg Cabinet. 16.

https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cabinet/16

Document Type

Image